Petrochemicals industry is starting to evolve

Steps have been taken to get around the region’s gas shortage, but competitive threats remain

The seismic shift in the GCC petrochemicals sector that consultants and analysts have been predicting for more than a decade is happening: we have entered the mixed-feed era. The latest sign came this month as Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc) confirmed that the next phase of its Borouge joint venture with Austria’s Borealis would include a mixed-feed steam cracker.

The announcement comes less than a year after Sadara Chemical Company (a joint venture of Saudi Aramco and the US’ Dow Chemical) brought online the GCC’s first mixed-feed cracker at its $20bn project at Jubail in Saudi Arabia. Aramco and France’s Total are also reported to be discussing a mixed-feed venture at Jubail. Elsewhere, Kuwait and Oman are looking to follow suit with their respective integrated refinery projects at Al-Zour and Duqm.

It is an important juncture in the evolution of the region’s petrochemicals industry, which was built on capturing previously flared gas to make low-cost commodity chemicals for export markets. It is change that has been driven because there is little ethane available for new petrochemicals projects due to a rapid rise in domestic demand for gas, especially from utilities.

With predictions that we may never see oil prices above $100 a barrel again, there is some happy coincidence in the timing of this shift towards mixed-feed. Governments will not be pumping expensive naphtha into chemicals production.

That is not to say the collapse in oil prices has not damaged the region’s petrochemicals industry. It has been a torrid couple of years for GCC producers, who have found their margins squeezed by the twin challenges of lower sales prices and rising competition from Chinese and US production in particular.

With fixed-price feedstock, ethane-based producers in the GCC have had their cost advantage eroded by the fall in petrochemicals prices since 2014, while their European and Asian counterparts, who derive their production from naphtha, have seen input costs more than halved. The days of effortless leaps in income on the back of soaring oil prices are over; instead most producers are reporting declining sales and profits.

Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (Sabic), the region’s largest listed firm, saw revenues fall by more than 10 per cent in 2016, and profits drop by nearly 5 per cent. Saudi producers have had to face the added challenge of a more than doubling of the ethane feedstock price at the start of 2016 to $1.75 a million BTUs, from the long-standing fixed price of $0.75 a million BTUs, as the government looks to rein in subsidies.

Operational excellence

The business response has been to create operational efficiencies and where possible raise output. Sabic, for example, says it has looked to take costs out of the supply chain, reduce unplanned shutdowns, optimise manufacturing and be more strategic over pricing.

“There is no other option but to aim for operational excellence,” Abdulwahab al-Sadoun, secretary-general of the Gulf Petrochemicals & Chemicals Association, tells MEED. “They need to trim the fat; it is a very competitive landscape. They need to consider consolidating assets, shared utilities, and look at procurement practices in order to cut costs.”

Those that are able to achieve operational excellence will emerge as stronger and leaner outfits, but they will still have competitive threats to face.

Beijing’s drive for self-sufficiency is the biggest concern for GCC producers as China consumes 20 per cent of the region’s chemicals exports. The UK’s ICIS Chemical Business reports that at least 10 new naphtha crackers could come on stream there by 2021-22. China’s ethylene capacity is expected to reach 37 million tonnes a year (t/y) by 2025, up from 23 million t/y in 2016, while propylene capacity is projected to hit 45 million t/y by 2025, up from 25 million t/y. China’s propylene self-sufficiency is forecast to rise from 82 per cent in 2016, to 92 per cent by 2020.

“GCC producers need to find a replacement [for China],” says Al-Sadoun. “Among the other markets that have potential is Africa. The infrastructure there is underdeveloped and there is high population growth. There is also a lot of growth in demand for fertilisers.”

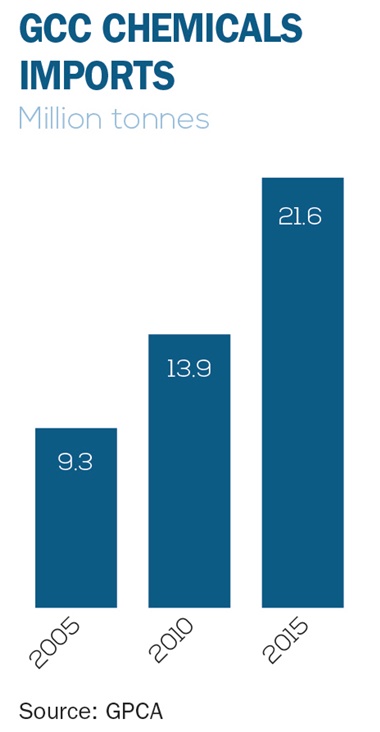

He says there is also an opportunity to use more polymers domestically by developing downstream sectors and substituting imports. “In 2015, chemicals imports to the GCC totalled $25bn; we can capture this by developing specialty or performance chemicals,” says Al-Sadoun.

In this respect too, the timing of the move to mixed-feed ethane/naphtha crackers can be considered fortuitous, as they facilitate a much broader product slate. Fourteen of the 26 manufacturing units located at Sadara’s giant complex will produce specialty chemicals and plastics products previously only available through imports to the region. Sadara is also developing an adjacent site to host downstream manufacturing and conversion industries, known as PlasChem Park. Investors have already come on board to produce hydrocarbon resins and surfactant solvents.

At present, it is only Saudi Arabia that has made tangible progress in establishing downstream conversion capabilities. This will be the next phase in the maturing of the region’s chemicals industry, now that the shift to mixed-feed is under way. In the process, the sector’s contribution to diversification and job creation will multiply. But the key will be finding new export markets to absorb the additional production.